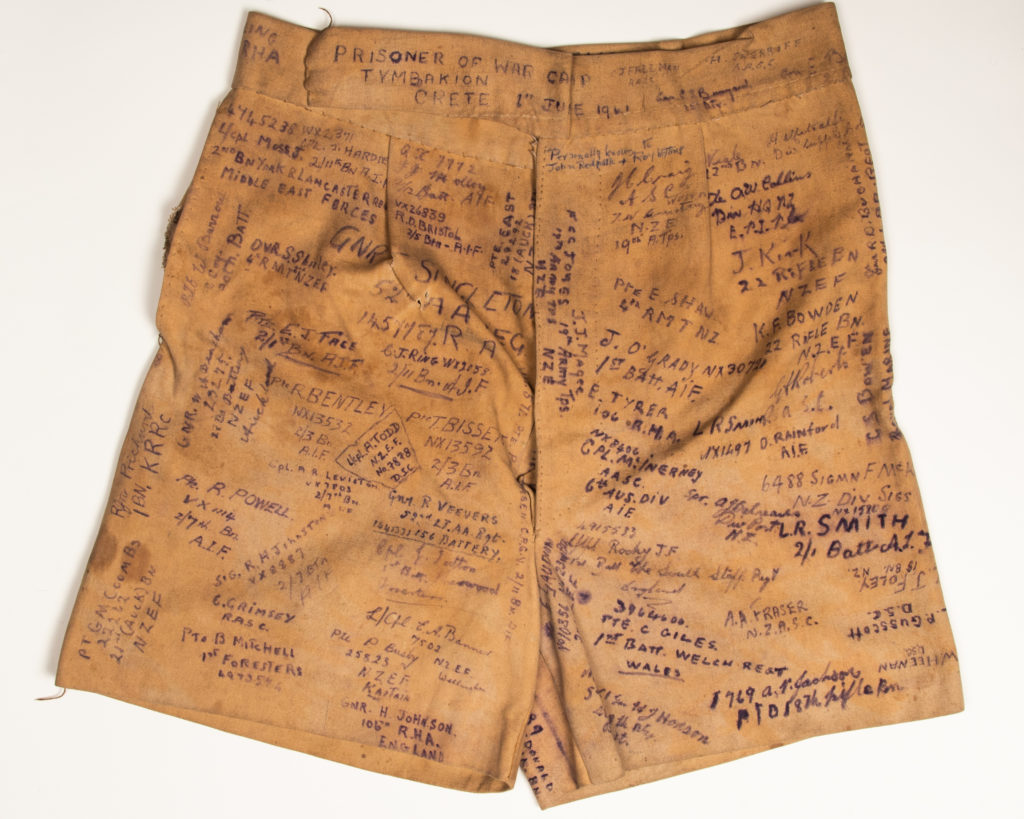

127 Prisoners of War and One Pair of Shorts

Can you help us give life to these 127 World War II soldiers and the story of the pair of shorts?

Tymbakion shorts project by Andrew Holyoake of NZ

A pair of shorts professionally crafted was brought back from WWII by Private Albert (Bert) Edward Chamberlain. As a civilian he was a tailor and would have had little trouble turning a sheet of canvas into a pair of shorts. Bert was a driver in the 2NZEF and was captured in Crete sometime in 1941.

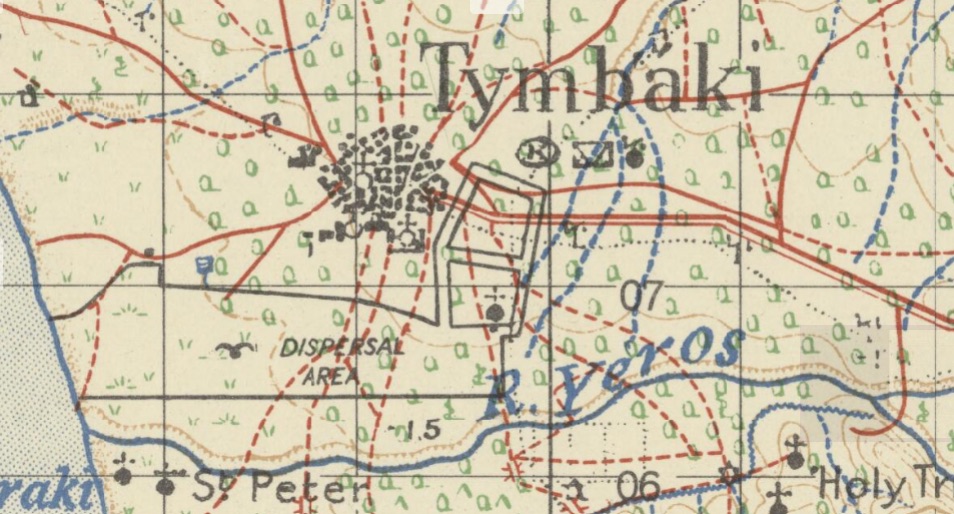

In the later months of 1941, the Luftwaffe set about developing an airfield in the south of Crete, close to the town of Tymbaki (Tympaki). This airfield, Tymbakion, still exists today. An Allied Air Intelligence report from 1943 suggests that the airfield was developed rapidly in the autumn of 1941 by utilising British and Greek POW labour gangs, who worked day and night. We think Bert was one of the men who was working on this aerodrome as a Prisoner of War.

At the beginning of 1942 Bert and others were shipped off to Germany and spent most of the remaining war years interred at Stalag VIIIB, Lamsdorf (also known as 344). He survived the war, returning home to New Zealand.

The shorts contain the signed names of 127 men. A couple of men, whose names appear on the inside rim of the shorts are men whom Bert was friends with at Lamsdorf. The others, however, in addition to the inscription “Prisoner of War Camp Tymbakion Crete” are an enigma.

One of the aims of this project is to find out if these shorts represent a partial list of those Allied and Greek POWs who laboured to build the Tymbakion airfield in late 1941. We are seeking evidence from written anecdotes and diaries, in addition to compiling circumstantial evidence, for example:

Within the Australian Red Cross POW cards that are held in a University of Melbourne Archive there are a few references of Australian POWs sending mail home from a camp at Tymbakion in September 1941. The majority (but not all) of these men’s names are on the shorts. www.archives.unimelb.edu.au

The majority of allied POWs captured on Crete around 1 June 1941 seemed to have been shipped to mainland Europe by August or September, 1941. We are looking for any information about these men and the dates they were transported from Crete.

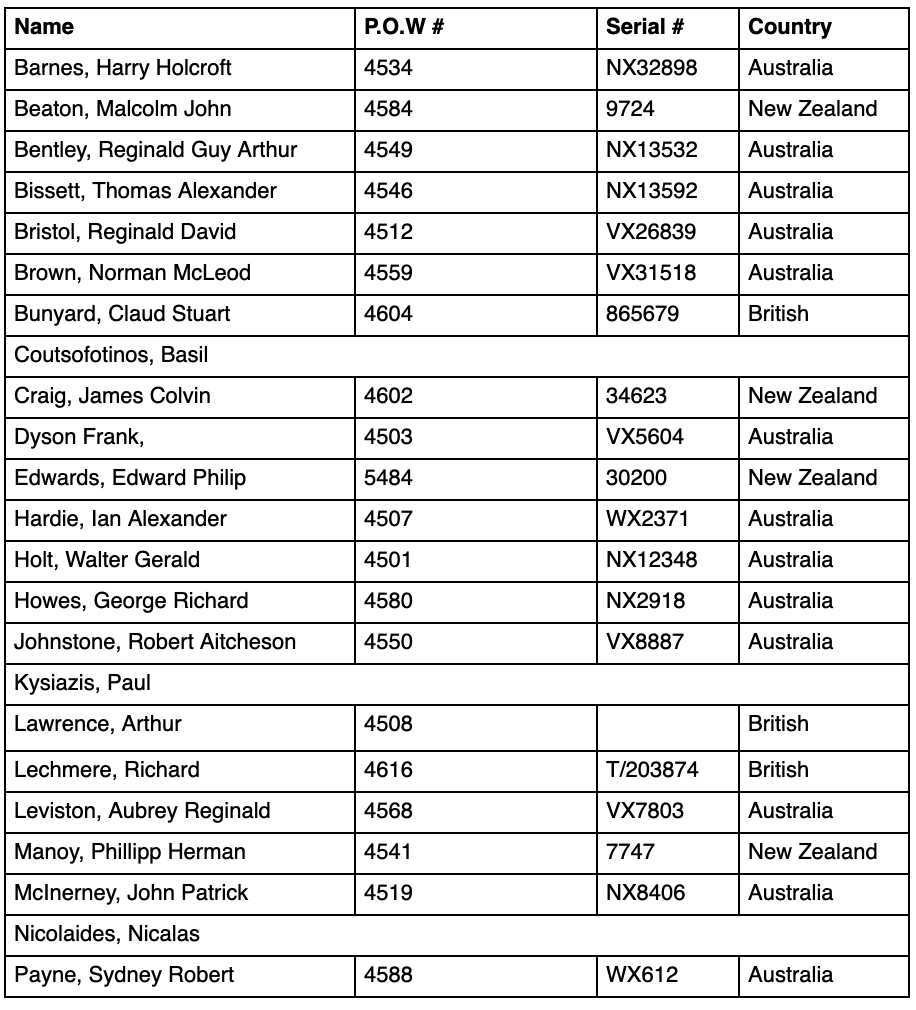

Below is a list of the men from the shorts, that we have basic information on, who may have been involved at Tymbakion (excluding those who were Bert’s friends at Stalag VIIIB, Lamsdorf (also known as 344). The names are arranged alphabetically in the following format: (surname, initials or first name, service number, POW number, country of service).

There are a few other names on the shorts that we are still working on.

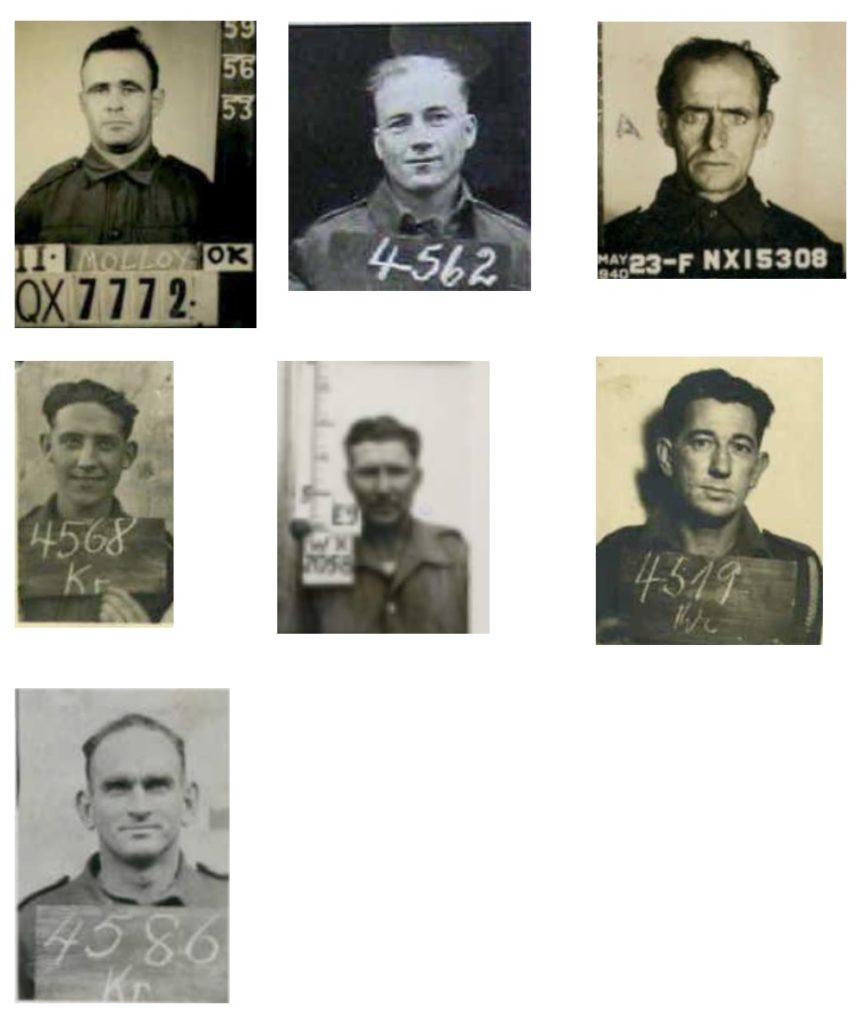

From top left to right top to bottom:

Molloy, John Joseph, QX7772, 4603, Australia

Buirchell, William Roy, WX2280, 4562, Australia

Smith, Loris Richard, NX15308, 4521, Australia

Leviston, Aubrey Reginald, VX7803, 4568, Australia

Ring, Cyril WX2058 Australia

McInerney, John Patrick, NX8406, 4519, Australia

West, Leonard Gordon, VX5561, 4586, Australia

Main List Below

Ainsley, John, R, 105991, 4556, England

Armitage, Thomas Washer, 33221, 5252, Sapper NZ Engineers,New Zealand

Baker, Edward, 2065377, 4596, England

Banner, Ernest Ambrose, 7502, 5012, New Zealand

Barnes, Harry Holcroft, NX32898, 4534, Australia

Barrow, William, 14244, 5458, New Zealand

Beacham, William Albert, 23275, 5227, New Zealand

Bennison, Avery Francis, 5353, 5350, New Zealand

Bentley, Reginald Guy Arthur, NX13532, 4549, Australia

Bissett, Thomas Alexander, NX13592, 4546, Australia

Bowden, Kenneth Frank, 30242, New Zealand

Bowen, George Stanley, CH/X101376, 4606, England

Bristol, Reginald David, VX26839, 4512, Australia

Brodie, Charles William, 13803, 23552, New Zealand

Brown, George Robert William, 2393, 5441, New Zealand

Brown, Norman McLeod, VX31518, 4559, Australia

Brownlie, Robert Bould, 4446, 5409, New Zealand

Buchanan, Roy Douglas, VX32961, 4607, Australia

Buirchell, William Roy, WX2280, 4562, Australia

Bunyard, Claud Stewart, 865679, 4604

Busby, Ponaute, 25823, 5443,28th Maori Battalion, New Zealand

Carter, Edward S, S/94334, 4560, England

Chappell, Ronald John, 7347150, 4510, England

Christiansen, Harold (Harry) Anthony, 30695, 5419, NZ Petrol Company,New Zealand

Collins, Andrew Walter, 5721, 24196, 2 Divisional Employment Platoon,New Zealand

Coombs, Gordon Maxwell, 22262, 5082, 21st Battalion,New Zealand

Cooper, Charles George, 5566, 5164,19th Battalion, New Zealand

Cooper, Hans John, 7347238, 4509, England

Craig, James Colvin, 34623, 4602, New Zealand

Crawford, J, 408857, 4578, England

Davenport, Joseph, 7259305, 4555, England

Davis, J. R, England

East, Edward, 29292, 5201, New Zealand

Face, Edward John Sydney, NX11441, 4585, Australia

Foley, Zamoni James Joseph, 2996, 5200, New Zealand

Forbes, Archibald Henry, 6912, 4511,30th Battery NZ Artillery, New Zealand

Foxon, T.V, 890183, 4582, England

Fraser, Anthony Alexander, 30024, 5417, New Zealand

Freeman, Clifford James, 148521, 4545, England

Gaudion, Eric John Robertson, 10356, 5203, New Zealand

Giles, C, 3964606, 4530, Wales

Goodwin, Edgar G, 1428576, 4565, England

Gorton, John, T/190420, 4544, England

Grimsey, Cyril James G, 148404, 4516, England

Gusscott, Louis Patrick, 33096, 5017, New Zealand

Hardie, Ian Alexander, WX2371, 4507, Australia

Harman, Geoffrey Bertrand, 4321, 5396, New Zealand

Harrington, Stanley Richard, 32257, 5412, New Zealand

Hastie, Alexander Brown, 33750, 5257, New Zealand

Heenan, Colin William, 8571, 5411, New Zealand

Herbert, Cyril M, S/154217, 4539, England

Hewett, Arthur, 2197321, 4576, England

Hodson, Herbert Joseph, 20661, 5437, New Zealand

Holmes, Howard John, 37054, 5119, New Zealand

Holt, Walter Gerald, NX12348, 4501, Australia

Howes, George Richard, NX2918, 4580, Australia

Hurren, Frederick Henry, S/94377, 4504, England

Jackson, Alexander Peter, 1769, 5424, New Zealand

Johnson, Henry, 888099, 4563, England

Johnstone, Robert Aitcheson, VX8887, 4550, Australia

Jones, Frederick Cyril Charles, 34810, 5302, New Zealand

Kirk, James, 30071, 4593, New Zealand

Kollias, Anastasios, Greece

Lechmere, R.J, T/203874, 4616, England

Leviston, Aubrey Reginald, VX7803, 4568, Australia

Lythgoe, Frederick (AKA Rocky), 4915533, 4547, England

Magee, John James, 32086, 5496, New Zealand

McDonald, Leonard Edwin, 22289, 4566, New Zealand

McInerney, John Patrick, NX8406, 4519, Australia

McKain, Frederick James Dunmore, 6488, 4520, New Zealand

McLean, Alexander, 7902927, 4506, England

Miller, John Walter, 7527, 4608, New Zealand

Mitchell, Bernard, 4973574, 4573, England

Molloy, John Joseph, QX7772, 4603, Australia

Moss, John, 4745238, 4536, England

Neale, Roy Errol, 5736, New Zealand

Nuttall, James, 902868, 4522, England

O’Grady, James Clyde, NX30721, 4597, Australia

Osborn, J.J, 6898510, 4595, England

Palmer, T.G.W, 7347235, 4526, England

Pearce, Sydney Emden, NX33248, 4518, Australia

Pedersen, Walter Vernon, VX5571, 4515, Australia

Pestell, R.G, T/73338, 4528, England

Petersen, Charles Amos George (Vic), WX571, 4538, Australia

Petrou, Ioannis, Greece

Pooley, A.E, 210653, 4583, England

Powell, Ray Edward, VX1114, 4569, Australia

Prichard, Jack H, 6849702, 4600, England

Pullenayagam, Joseph Patrick, 7297, Sri Lanka

Pyatt, E, T/182533, 4558, England

Rainford, Douglas, NX1497, 4601, Australia

Rattenbury, John Alfred, NX6877, 5331, Australia

Rees, Edward, 13237, 4591, New Zealand

Rice, F.J, T/117358, 4594, England

Ring, Cyril James, WX2058, 4540, Australia

Roberts, G.A, 132569, 4615, England

Rogers, J, 148797, 4557, England

Shaw, Ernest, 8613, 4525, New Zealand

Sherriff, Harold, 10670180, 4502, England

Shirley, Stanley, 9036, 4533, New Zealand

Singleton, Jack, 1457787, 4537, England

Skinner, J.E, 218039, 4542, England

Smith, Loris Richard, NX15308, 4521, Australia

Stirling, Leslie Douglas, 6846877, 4517, England

Stratton, Herbert Ernest, WX547, 4561, Australia

Stubbs, Arthur Gordon, 4379, 5508, New Zealand

Stuckey, John Edward, NX11243, 4567, Australia

Tatton, John Thomas, 4973903, 4571, England

Thompson, J, P/SSX20790, 4551, England

Todd, Arthur Skuse, 7272, 7878, New Zealand

Topia, William, 22724, New Zealand

Tyrer, E, 905373, 4579, England

Veevers, R, 1441331, 4552, England

Walker, D.A, T/111909, 4572, England

Walters, F, CH/X3473, 4543, England

Warburton, H, 1058195, 4554, England

Weatherall, William, 862968, 4535, England

West, Leonard Gordon, VX5561, 4586, Australia

Whatling, Clive Joy, 902385, 4599, England

Whitcombe, John Douglas, 22768, 4605, New Zealand

Woods, Laurience Samuel, WX443, 4564, Australia

Wynn, Thomas Peter, 898637, 4577, England

If you recognize any names on this list, and can help with this, please make contact with us at Tymbakionshortsproject@gmail.com

Andrew Holyoake (New Zealand), Tony and Deb Buirchell (Australia).

Thanks to Mike Smythe for hosting this search, and to Mitchell Adair for the photography.

UPDATE 2/08/21

Tony and Deb Buirchell have been inundated by interested people whose relations were in the Australian Military Forces who fought on Crete. Over 25 replies were received as a reaction to three advertisements in the local Western Australian newspaper in a section called ‘Can we Help You”.

The main questions the Project is hoping to answer are:

1. Who made the canvas shorts and where were they made?

2. Where were the canvas shorts signed?

3. What was Tymbakion?

4. What do we know about the men who signed the canvas shorts?

A comprehensive diary by Charles (Vic) Petersen, WX571 came to light thanks to Sue and Grant Petersen. It covers every day of Vic’s incarceration from June 6th, 1941 to his release from a POW camp in 1945

Another diary kept by Ian Alexander Hardie WX2371 is being followed up thanks to Ian’s two daughters Helen and Janet.

From the Vic Petersen diary it has been found that what may be the final group of allied POWs left in Crete were rounded up on 11th September, 1941 and embarked on the ship Norburg in Souda Bay. The men were taken to Iraklion before being sent in trucks over the mountains to the southern side of Crete. Here they were imprisoned at a place near the town of Tympaki.

A study of the Army Records and Red Cross Cards for all the Australian signatories on the shorts showed that Tymbakion was mentioned 18 times leading to a possible place where all the men on the shorts may have been together.

Vic talks to being forced to pull out ancient olive trees to make an aerodrome runway. After four months the men were taken by truck to Souda Bay. From here they sailed to Salonika and then put on trains to a range of Stalags in Germany and Poland.

The answers to the original questions are somewhere in these movements. The search goes on, can you help?

If you recognize any names on this list, and can help with this, please make contact with us at Tymbakionshortsproject@gmail.com

UPDATE JUNE 2022

Prisoners of War Crete 1941 – 1942, Tymbakion and a Pair of Shorts

By Andrew Holyoake

Official accounts of POW life on Crete mostly relate to the period between capture (centred around 1 June 1941) and the majority of POWs being sent off Crete by the end of July 1941. There is a lot of contemporary literature describing the initial rudimentary conditions of the ‘Galatas camp’, the use of POWs in ways that contravened the Geneva convention, the lack of food and other supplies that meant that POWs were allowed (even encouraged) to locally forage etc. Sometime in these first few months a number of things occurred. Firstly the seriously injured and majority of officers were flown off (within days/weeks). Secondly, a series of 5 sub camps were set up, segregating nationalities.

Thirdly ‘infrastructure’ arrived (tents, food etc), and the perimeters became less ‘leaky’, as the monotony of camp life started to set in. Capture cards were filled in towards the end of June and again around the middle of July, but these seem to have been posted from Stalag VIIIB in around October, thus there was no word on the fate of these men other than word of mouth from those who managed to escape/evade and leave Crete safely. By mid-July, however, large cohorts of men were being shipped off Crete to Piraeus (where they may have first interacted with the Greek Red Cross), on to Frontstalag 183 at Salonika and then generally rapidly onto their main Stalags in mainland Europe.

The POW designations of these men today, are from formal processing at their destination camps (Stalag VIIIB , Stalag VIIA etc). A well-documented illness outbreak in the camps put paid to POW shipments for a while, but by mid-August, thousands more men embarked on this journey. The POW designations of these men (from this August shipment) today, are from formal processing at Frontstalag 183 (Salonika).

By the start of August the Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta (Dulag Kreta) camp had a postal service (with its own feldpostnummer (postcode)), and mail was being sent by POWs (sometimes arriving home before the aforementioned capture cards). The Red Cross still had no presence on Crete and there does not appear to be any firm numbers/record of men who were still on Crete in captivity. An indeterminate number of men were being treated in hospitals on Crete (both within camp and in towns) and many men were still being captured, having evaded capture for months. Escapes from captivity were also still occurring.

By the start of September, organised large scale shipments of men seem to stop. There were possibly <1000 men still on Crete in captivity. These men were formally processed (fingerprinted, photographed, and recorded on Personalkartes) on Crete and were issued Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta POW tags, with unique numbers within two number ranges. Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta numbers in the range 4xxx were issued to men who were being held in Lager Kreta V, whereas Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta numbers in the range 5xxx were issued to men who were being held in Lager Kreta VI.

Tying these designations to specific locations has not been possible yet. It’s possible that Kreta V and VI were different ‘ranges’ of the same large camp, as by this time, the written history suggests that nationality-specific camps such as the AIF one at Skines had been closed and all men were brought together at one place (presumably at, or close, to the original camp site). Mail home from Crete in this period still talks of the men swimming daily.

There is ongoing work to understand just who the men issued with Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta numbers were and how/when they were shipped off Crete. New Zealand Newspapers reported in November 1941 that in late October 1941 there were 735 POWs in captivity on Crete, and by February 1942 there were 3. It is not known if this includes all Allied POWs, or just New Zealanders, but the assumption is the former.

The current ‘confirmed’ list includes New Zealanders, British, Australians and Greeks, but will likely also include Cypriots, those within the Palestine forces, and potentially Russians. It is unknown at this stage if merchant seamen (including a number of Lascars) were also issued Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta numbers. Those with Kreta numbers also appear to fall into three broad categories: long term captives, who went ‘into the bag’ around 1 June 1941, and remained in camp; the injured who were retained in hospitals and infirmaries in Crete; and the recently captured/recaptured, many of whom gave themselves up so as to not endanger their Cretan helpers, and/or (in at least one case) so that their parents would know they were alive.

The proportion of each group within the ‘kretas’ is unknown, but anecdotally, it’s possible the third category dominate. At this stage there is scant evidence of POWs being shipped off Crete en masse in September, October or November 1941.

In the middle of September there was a ‘hospital shipment’ that were processed at Stalag VIIIBIn mid-December a number were shipped out of Heraklion, but these may have been being shipped back to Souda Bay. It appears that the last significant shipment of POWs out of Crete was on, or around, the start of January 1942 from Souda bay to Piraeus.

Interestingly the men still on Crete in September who were issued Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta numbers were not a random assortment of all of the men captured on Crete. An analysis of the NZEF POWs from Crete shows that there are a significantly higher proportion of Sappers (engineers) in this group than in the groups shipped off Crete earlier, and a significantly lower proportion of Gunners in this group than in the groups shipped off Crete earlier. Given that is within one nationality, this does not appear to simply be a nationality bias. However, as above, as this group includes long-term captives and recent captives, it may be self-selecting.

It’s possible that POW labour needs are a partial reason that there is an apparent distortion in the types of men who were on Crete for longer than others. POW labour was a part of captive’s lives from day 1. Initially POWs were burying the dead, moving supplies from Allied stores, moving planes off the Maleme airfield, and gathering food. It is important here to also not conflate Allied POW labour, with the forced Labour that was being inflicted on the local populous. This Cretan forced Labour was on a massive scale and key to the German command creating the ’Island fortress’ they were after.

There is little in the written record of later Allied POW labour, and much of what is written here is gathered from first-hand accounts. Letters home and recorded in the NZ newspapers talk of men working on a ‘war memorial’; likely the Fallschirmjäger memorial three kilometers west of Chania on the road to Agii Apostoli. Others were on ‘day parties’ from Dulag Kreta engaged in a whole range of the other activities. One even talks of driving a truck. The men were able to receive mail, and were paid (so as to not contravene the Geneva Convention). Dulag Kreta was likely feeling more like a permanent Stalag. Life was certainly not easy though. Escapes were still attempted (attempts increased towards the end of December 1941 as men became aware that shipment off Crete loomed) and men were being shot and killed during failed escape attempts in this period.

Not all Allied POW Labour in this period, however, was occurring close enough to Dulag Kreta to enable this to be the only overnight base. At the start of September 1941 around 200 POWs (New Zealanders, British, Australians, and Greeks) were trucked to the south coast of Crete to work on the Tymbakion aerodrome, and at some stage it was likely that a similar camp was set up in the vicinity of Heraklion to work on the airport at Heraklion. It is possible that other ‘satellite’ camps were set up on a temporary basis as well (eg Kastelli?). The Tymbakion satellite camp was occupied by Allied POWs for 3.5 months. I would note, however, that the activity the POWs were engaged in at Tymbakion likely contravened the Geneva Convention as, by developing the aerodrome, they were directly contributing to the Axis war effort. The men were being forced to work (at gunpoint), but at the same time were perversely receiving a small wage. Active and passive resistance was common. The Tymbakion story does not stop when the Allied POWs were trucked back north on the 28th of December 1941. Rather, the local populous was forced into Labour (by February 1942), and the stone/masonry built town of Tymbaki was deconstructed to be used as base course for the aerodrome runway. This later legacy is still very raw within Tymbaki today.

The majority of the Tymbakion POW story to date has come from the diary written by Private Vic Petersen WX571. Rather than surrendering, Vic took to the hills on 1st June, 1941. He and the others in the small party were rounded up by the Germans a few days later and marched, under duress, back to the main holding Camp. There he remained, until 26th August, 1941 when there was rumour of a movement to a new location. On this day he recorded in his diary that, “Boys making hats and trousers out of tent as clothes wearing out.”

On 5th September, 1941 Vic Petersen and his group were placed on board a ship in Souda Bay and sailed to Heraklion. From this Cretan town the group was moved by truck, over the mountains to the location of Tymbakion. Here the men would be used as slave labour clearing hundred year old olive trees and extending an aerodrome.

Although the aerodrome was established by the British pre-war it was little known around the World. The Germans were adding to the site so that they could land and refuel their bombers thus allowing them to reach Alexandria, Suez Canal and the oil fields of Iran.

This job was daily until 29th December, when the camp was abandoned and the prisoners, made up of Australians, New Zealanders and British, were trucked back to Souda Bay to start their journey through Salonika and on to Stalag VIIIB in Lamsdorf. From Souda Bay the group were shipped in an Italian convoy to Pireaus and on a Bulgarian ship to Salonika, arriving at Salonika 9th January, 1942. A week later and after suffering the shocking conditions of Frontsalag 138 they were crammed on a train on 15th January, 1942 (the dead of winter) which headed north for Germany.

To date, other than Vic’s diary, and the shorts that sparked this whole interest, a Tymbakion POW camp has appeared to be a mirage. It gets one word mentions in Red Cross Cards, diaries, repatriation questionnaires, Casualty cards, Personalkartes, war records etc. Gradually, however, we are building up a picture of who was there, what infrastructure was present, what the men were doing, and how they were part of a wider Tymbaki story. At the same time we are connecting with many families of the ‘kreta’ men and both sharing and gathering stories….

Building a case for a Tymbakion POW camp.

Update July 2022

The first notion I had that there was an allied POW camp at Tymbakion came from the shorts that started this project. However, the shorts are a partial red-herring, in that not all men on the shorts were at Tymbakion, and not all men at Tymbakion were on the shorts.

Nonetheless, by attempting to contact the families of the men who signed the shorts, a Tymbakion story has emerged.

A major breakthrough came when the family of Vic Petersen shared his POW diary. Vic was at Tymbakion POW camp from its inception to its closing and to date provides the only first-hand account of this camp.

The second major breakthrough was the family of Richard Lechmere sharing letters that he wrote home to his wife and daughter in the UK from the Tymbakion camp. Whilst they paint a rosy picture of life, they also provide some corroboration of information gleaned elsewhere.

The third substantive breakthrough was the family of Jimmy Craig sharing some information that likely came from an address book of Arthur Lawrence.

Other information referenced below comes from Red Cross cards held in the University of Melbourne digital archive, AIF casualty cards from the digital archives of the Australian War Memorial, and first-person POW Repatriation Forms held in the UK National archives in Kew, kindly sourced by Philip Mills.

On around 5pm the 12th of September 1941 around 200 Allied POWs arrived in the vicinity of the town of Tymbaki (a.k.a Tympaki, Timbaki, Timpaki, Tympakion, Timpakion, Tymbakion, Timbakion, Τυμπάκι) on Crete’s south coast and were placed within a pre-existing 7-8 foot high barbed wire, fenced compound. They pitched tents and sourced water from a drain, indicating that there was little other pre-existing infrastructure.

Vic talks of walking 3 miles from the camp to work at the Tymbakion airfield site, but the exact location of this camp is still obscured.

The primary objective of this labour was to clear olive trees to create a flat runway for an aerodrome. The men were well aware, and protested, that the work that they were being made to undertake contravened the Geneva convention, as it directly supported the war effort, but as Vic writes on November 15th, ‘…again working on aerodrome, under protest, and threatening to shoot ten men if we refuse to work, and of course men with rifles prevailed…’.

Whilst evidence is hard to find, it is likely that the British had created a rudimentary runway here prior to the German invasion, but the Germans recognized its strategic importance and dramatically expanded this. Vic talks of planes landing within 2 weeks of the work starting.

The current airfield at Tymbakion is on the site of this work and has basically been in continuous use since 1941. The current airfield has both a North/South runway (along the beach frontage) and an East/West runway. Whilst current evidence is scant, it is likely that the East/West runway was the first to be developed (and the one that the POWs worked on) and the North/South one is a later effort that was expanded by local forced labour in early 1942.

1942 1:50,000 Crete / reproduced by 512 A. Fd. Svy Coy, R.E. from a Greek 1:50,000 map dated 1939 ; revised from air photographs & reprinted by 512 Fd. Survey Coy., R.E. October, 1942-43

In 1942, when the local forced labour was press-ganged into work to further develop this airfield, there were a number of Greek engineers involved. Vic does mention engineers being in charge of the work in his diary in 1941, so it seems likely that this was a planned, designed, and managed effort.

In addition to the airfield, in the months following their arrival, the allied POWs were also repairing roads and bridges, and generally ‘improving’ the infrastructure required to support the airfield.

The airfield was latterly home to a number of German units and defences, and there were permanent buildings, fuel dumps, and defences present, but there is, as yet, no indication of precisely when these were built (and Vic dos not talk of them).

This camp was the home for POWs from mid-September 1941 until the end of December 1941. There is no evidence yet of how the Germans classified this camp. It has not been associated with a known ‘E’ number like Arbeitskommandos in mainland Europe, but was likely considered a subcamp of Kreigsgefangenenlager Kreta.

In a letter home from Tymbakion in December 1941, Richard Lechmere included his postal address as 46234-T. 46234 was the Feldpost nummer (essentially a German military postcode) for Kriegsgefangenenlager Kreta (30.7.1941 – 28.2.1942) so it is very likely that 46234-T indicates a mail bag destined to Tymbakion from Kriegsgefangenenlager Kreta.

As above, mail was being sent and received from the Tymbakion camp. Remarkably on the 18th of December Vic writes in his diary of “6 English letters arriving in camp today”, and corroborating this, on the 21st of December Richard Lechmere writes to his wife recounting receiving mail from her three days prior. Frustratingly to date, it has been very difficult to pin down just who was at Tymbakion. During his time there, Vic mentioned no names in his diary, but does reference a few later in 1943. The makeup of the initial approximately 200 men is largely unknown but likely includes British, New Zealand and Australian POWs, primarily from Kriegsgefangenenlager Kreta V. Vic does talk of RAF men being “taken off the job and flown to Athens” in the second week of October, but their identities are currently obscure. It is highly likely, however, that one of these men, was Jacob Gewelber, a Palestinian/Polish Jew, and member of the 33 Sqn RAF Maleme ground crew captured on 23rd May 1941. He became ‘Jack Gilbert’, with POW number 4027. Vic talks of a number of Greeks in the camp, but it is unknown if these are only combatant POWs, or included locals and if these are included in the 200 or not. Later a further 50 POWs arrived. A Special Operations Executive report in January 1942 from Captain C.M ‘Monty’ Woodhouse recounts 14 lorry loads of POWs being driven back north on the 28th of December (on the corresponding day that Vic recounts in his dairy) and puts the numbers at between 150 and 200. We currently have primary (or secondary) source evidence for 31 men being at the Tymbakion POW camp, but this list is growing.

An interesting aspect of the Tymbakion camp was the interaction with the local Cretans. Vic talks of locals bringing food to the camp on religious holidays and of placing food in the bowls of cut trees at the airfield worksite. This was for the POWs to find and eat when they came back to grub out the roots of the felled trees (that provided the locals livelihood). From the locals perspective this was probably just carrying on the long tradition of philoxenia. It is important, however, to consider this in a wider context. The POWs were not getting sufficient calories in camp for the work that they were doing, so their condition was deteriorating. The autumn/winter of 1941 was very cold, and following their stay here, all of these men were taken by ships to Salonika where conditions were shocking. Eventually they were placed in rail cattle cars in Salonika and railed to Lamsdorf. The conditions on these trains were horrific and a number of men perished though a mix of starvation and cold exposure. Thus, whilst it is conjecture to estimate the importance of the support the locals were providing these POWs, it is highly likely that this food supplementation kept many men alive. As it is, Vic talks of losing 1/3 of his body weight by the time he arrived at Lamsdorf.

To date little is known about camp ‘life’. Vic talks of some details, especially around having Sundays off, playing cards, food rations and poor clothing but others are emerging as well.

An interesting aspect is the presence of medical personnel.In his diary,Arthur Lawrence references Jimmy Craig as a “patient Tymbakion”.Similarly,on 12th February 1943,writing from Lamsdorf, Vick talks of running into ‘one of the medical orderlies from Tymbakion,his two mates in Poland looking after wounded Russians ‘.Lastly,the Red Cross card of Captain Walter Gerald Holtan an AIF doctor indicates that he was also at Tymbakion at this time .

Holt had previously been a doctor at the Canea camp Hospital at Agii Apostoli.

Update February 2024.

In trying to get to the bottom of just who was at Tymbakion, when they were there, where the camp was, and what they were doing, I’m leaving ‘no stone unturned’. Sometimes this has remarkable consequences. Via a circuitous route in late 2022, I was fortunate enough to receive from the ICRC a scanned 79 page German hand written ‘census’ of the Allied Servicemen men who were in captivity in Crete in late 1941. The census, conducted between December 7 and 14, 1941, has 770 entries of mostly British, Australian and New Zealand POWs. The census, however, does not likely tell the whole story. There are no Greeks in the census and accounts suggest that there were still Greek combatant POWs in captivity on Crete at the time. Likewise, there are no names of people who identified as PAL, and again records suggest that there were still a few PALs in captivity until early 1942. However, indications are that the census does broadly represent the UK/AIF/2NZEF story. Contemporary newspaper stories from this time suggest around 780 Allied POWs in captivity. Deciphering the hand written census (with each entry recording details such as camp, name, birthdate, service number and country, POW number, role, and capture place (sometimes)) has been a big effort that is now complete. Due to ICRC release rules the information can’t be shared in database/digital form, so what follows is a summary of the main information that has been gleaned from it to date.

Camps:

The census is divided into 4 camps, called Chania, Iraklion, Maleme and Tymbakion.

The Maleme camp is known having been mentioned in a few diaries, and by this stage the men were building air crew barracks, etc. It appears as though this camp an almost continuous POW presence from late May 1941 until late December 1941. The Chania camp is likely actually at the site of the original Galatas camp. The men here were on day release work parties, and/or not working, as this is also the place where recent escape/evader captures were housed. The Iraklion camp is still a bit of an enigma. It’s possible that the men were working on the airport, but there is also a strong association with a hospital (this Iraklion census uniquely has a subset of men with a ‘laz’ designation (short for lazarette) many of whom have been previously associated with Tymbakion). The Tymbakion camp has been covered above and later. Perhaps equally interesting is potential camp sites that are not recorded as holding men at this census. For example, there is compelling evidence for a brief labour camp associated with Rethymnon in September/October 1941, but by December these men are recorded at Chania. I’ve speculated above that there logically could have been a camp associated with the development of the aerodrome at Kasteli but this does not seem to be the case.

At the time of the census there were 87 men listed as being at Iraklion, 440 men listed as being at Chania, 125 men listed being at Maleme, and 119 men listed being at Tymbakion. One man appears on both the Iraklion and Tymbakion census.

POW numbers and Camps:

Maleme. The men at the Maleme camp represent two distinct phases. The almost continuous series of POW numbers 1445 – 1500 is only associated with the Maleme camp and the current theory is that these numbers were assigned at Maleme (i.e. it was a processing camp) This series is also associated with mail franked with Kriegsgefangenenlager Kreta (I) indicating that this was the camp designation. Almost all men with POW numbers in the 1445 – 1500 range are 2NZEF, and were either involved in transport as their civilian occupation, and/or in logistics as their service role. Thus we can speculate that this POW labour phase at Maleme was involved in driving. This is supported by a couple of letters home that describe a role driving, and the role that the airfield at Maleme had in supplying the troops in North Africa with provisions – there is evidence that the Germans stripped Crete of food to supply troops in North Africa. The rest of the men at Maleme are from the POW series 5000 – 5591. This series was assigned at the Chania/Galatas camp (Kriesgefengenenlager Kreta (VI)). These men would have been transferred to Maleme later, after processing at Chania. It appears as though these men were involved in construction, building wooden barracks for Stuka pilots.

Iraklion: Like Maleme, Iraklion seems to have two distinct groups of men. All 20 POWs with numbers between 4001 and 4434 are associated with Iraklion. The majority of these men were evaders captured as a big group in mid October 1941 in the Iraklion region, and they seem to have been retained at Iraklion rather the being sent on to Chania. It seems likely therefore that this POW range was issued at Iraklion. The camp designation is a bit unclear at this stage, as currently it’s only been associated with Kriesgefengenenlager Kreta (without a number suffix). Latterly, the Iraklion camp, and associated lazarette seems to also have a close association with Tymbakion. As below, Tymbakion had two phases. The first significant group (4500 – 4616) arrived (and were processed at Tymbakion) in September. At the time of census, 12 of these men were at Iraklion. A later group of men from the Chania (5000 – 5591 POW number series) were sent to Tymbakion in November, and at the time of census, there are 50 men from this series in the Iraklion Census. Not all of these men have been previously associated with Tymbakion, so it’s possible that not all of this Chania group went all of the way there.

Chania: The majority of men at the Chania Camp in December have POW numbers in the 5000 – 5591 series. This range was issued at Chania. Quite a few of these men were captured evaders, thus it seems that (other than Iraklion above) Chania was the main camp where these men were held and processed. The exception to this is the POW number series 3195 – 3211. These men appear to have been processed at Rethymnon (with a designation of Kriesgefengenenlager Kreta (III)) but by the time of the census this sub camp had closed and these men were back at Chania. Chania does not seem to have been as strongly associated with labour as Maleme or Tymbakion. Men talk here of not working, or of just doing day work.

Tymbakion: The 119 men associated with Tymbakion in the census are associated with two phases. It appears as though the group 4500 – 4616 arrived (and were processed at Tymbakion) in September. All of the men in this group are either associated with Tymbakion or Iraklion, and the majority of the men from this group in Iraklion have been previously associated with Tymbakion. It is likely that this POW number series was issued at Tymbakion, and this camp has been designated Kriesgefengenenlager Kreta (V). A second group of perhaps 50ish men arrived at Tymbakion later. This seems to loosely correlate with a cohort of men in Tymbakion at census time but with POW numbers in the 5000 – 5591 series. Within the 5000 – 5591 POW number series (issued at Chania) there are 50 men at Iraklion and 30 men at Tymbakion at the time of the census. As above, only some of these Iraklion men have been previously associated with Tymbakion, and Petersons Diary about Tymbakion only talks of 50 men arriving so it’s possible that some of these men never left Iraklion (Iraklion being the half way point between Chania and Tymbakion). Interestingly, a group of ~18 RAF men have been associated with Tymbakion as well and these men were all flown off Crete prior to the census. The ‘fingerprints’ of these men are still visible, as the POW numbers that they were issued on Crete were never re-issued, leaving conspicuous gaps in the census.

Nationalities:

The commonly held view regarding the numbers of POWs captured during the battle of Crete is of around 11,300 UK and dominion service men captured, comprising 2180 2NZEF, 3102-3169 AIF, and ~6000 UK. Within the census in December, there are 506 2NZEF, 99 AIF and 162 from the UK. Proportionally, this amounts to 23% of the 2NZEF, 3% of the AIF and 3% of the UK POWs still being present in captivity on Crete in December. The reason for this apparent ‘skew’ towards the 2NZEF is not known, but a number of non-mutually exclusive theories have been put forward.

Perhaps the 2NZEF were more inclined to work for incentives; perhaps they were more inclined to escape/evade, and therefore ‘missed the boat’, such that they were only recaptured after shipments of POWs off Crete were halted in late August. Perhaps also they had experience/skills of more use to the Axis than other nationalities. As men of the depression they were often from rural areas, and had a ‘can-do’, ‘number 8 wire’ attitude.

There are a few pieces of evidence that add weight to some of these thoughts.

Service role/Rank:

A brief analysis of the ranks of 2NZEF who were captured on Crete, both the overall 2180 and the 516 who were retained, has some interesting trends. The proportion of officers and gunners, as a percentage of 2NZEF POWs with these ranks out of all 2NZEF POWs, is lower in the December census than the proportion originally captured. This is expected for officers as it is well documented that officers were taken off Crete rapidly, but is less expected for gunners. Conversely, the proportion of Drivers and sappers is higher in the December census than the proportion originally captured. Given the Axis need for logistics and infrastructure on Crete, this may indicate that men were retained based on their skill set.

Escapers/Evaders:

An interesting element of the census is that for a subset of men their incarceration as POWs was brief, and this may be the only record. Towards the end of December, there appears to have been an active escape committee (see below) at the Chania camp that facilitated the escape of over 20 men. The majority of these men subsequently got off Crete to Egypt, and subsequently re-joined their units. Their POW numbers are recorded in the census and these numbers were never reassigned on Crete.

Likewise, in 1943/4, a number of ‘protected men’ and medically unfit POWs were repatriated from camps in mainland Europe. The WO416 personlkarte archive does not have cards for these men, and they do not appear on POW lists. Again this census has their POW numbers so is being used to update digitally accessible records.

In late 2023, another significant resource became publically available. Ancestry.com released digitised repatriation questionnaires of over 83,000 POWs. These questionnaires were filled in by POWs on return to the UK, and aimed to capture information on war crimes, escapes etc. Whilst these have been physically held in the UK National archives for some time, access to them has been dependent on a physical visit. An interrogation of these has identified that 1/3 of the 770 men in captivity on Crete in December have digitised repatriation questionnaires. A high proportion of these, especially within the Chania camp have mentions of escapes/evasion with subsequent recapture. Most of these escapes occurred within a few days of capture, with the recaptures occurring anytime up until the census date. Some men appear to be serial escapers (listing up to 4 escapes on Crete). This adds eight to the notion that many of these men were present simply because they were only recaptured after shipments of POWs off Crete were halted in late August.

These forms are a treasure trove of information. There are over 4,000 in the archive whose authors list Crete as the place of capture (the majority will have been taken off Crete early). Some interesting bits gleaned to date include:

- As above, the escapes at the end of December were non-random and appear to have been co-ordinated by Captain Kiernan Dorney, an AIF medic who was working in the old 7th General Hospital. He affected his own escape as well, alongside Major Arnold Gourevitch; both men go off Crete safely.

- Some of the men labouring at Tymbakion mentioned this as part of their work history on their forms. One, dryly, describes the cutting down of olive trees that they were engaged in as ‘forestry’.

Tymbakion specific update

As above, we are lowly getting a better understanding of the Tymbakion POW camp and the wider context of POW life in Crete at the time. We now have many more names associated with Tymbakion than were written on the shorts (close to 200). Other than digging into the lives of these men, and trying to connect with families; the other enigma we are currently trying to solve is precisely defining the location of the camp. This involves old maps, historical references, first-hand accounts, topography, archaeology and a lot of time on Goggle earth. We’ve narrowed it down to an area of just a few hundred square meters. Resolving this will likely be a significant aim for 2024, if we can get to Crete.

More updates coming in the future watch this space.